The Long Island Rail Road Trainmen's Trio

This musical trio was first organized in 1924 under the sponsorship of the

LIRR, with Jeff Skinner, Johnny Diehl and Matty Balling. They were

very popular, performing at various public and railroad-related events. They

lasted into the early 1930s with Johnny Diehl being replaced by Charlie

Burton after Diehl was let go from the railroad.

Jeff Skinner, born in 1900, joined the railroad for summer employment in

1917,

and "stayed on for 47 more summers" as he used to say. He started as a

"guard" who was a member of the train crew who used to open and close the

doors and platform guards (traps) on the passenger cars. He eventually

advanced to trainman and conductor.

I met Jeff in 1969 after he was retired and writing the Veterans column in

the LIRR newsletter "MetroLines" and he and I became very good friends.

On one occasion, around 1971,we even performed, together, a number of his

old Trainmen's Trio songs at a meeting of the Long Island Sunrise Trail

Chapter of the N.R.H.S. in Babylon. He played the guitar and we both sang

and harmonized.

Jeff was a great influence to me and my railroad interest and he was missed

terribly by many besides myself when he died in 1976.

|

Jeff Skinner Collection |

Song Sheets

"Living on Long Island"

copyright 1947

"Somewhere Along the Sunrise Trail"

copyright 1926 |

|

Jeff Skinner Collection

Jeff Skinner Collection

Jeff Skinner Collection |

Communication Failure

This photo, taken by the late Thomas R. Bayles, who was a Long Island Rail

Road ticket clerk at the time, is of E51sa (4-4-2) camelback #4 westbound at

Speonk in 1915.

As one can see, a camelback locomotive differs from a regular locomotive in

that the cab was astride the boiler. The engineer sat on the right

side of the boiler, cut off from the fireman who sat on the left side when

he wasn't shoveling coal into the always-hungry firebox. There were no

radios, so communication between the two enginemen was practically nil.

Retired Long Island Rail Roader George G. Ayling, who was assigned to the

Cental Islip station for many years, both as block operator and later as

agent told me this story.

It seems a Main Line passenger train, pulled by a camelback locomotive was

scheduled for a station stop at Central Islip.

When the train didn't appear to be slowing for the station, the fireman got

a little concerned. When the train ran both the station and the stop

block signal, the fireman thought he had better go see what was going on and

be quick about it!

He got out of the cab on his side of the boiler, walked along the catwalk,

around the back of the locomotive and along the catwalk on the engineer's

side of the locomotive.

When he got to the cab, the engineer was slumped over the throttle, dead.

It was later determined that he had a stroke. The fireman brought the

train to a stop.

Thank God the fireman position wasn't abolished all those years ago!

|

E51sa (4-4-2) camelback #4

westbound at Speonk in 1915

Photo: Thomas R. Bayles

Dave Keller Collection |

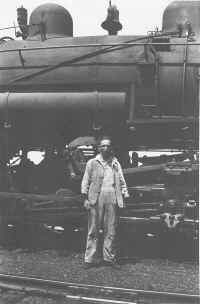

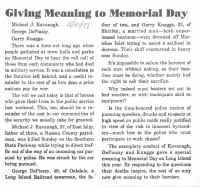

Charlie

Jackson, Engineer

Charles T. Jackson was born in 1895. Both his father, Coe Jackson and his

uncle, Parmenus Jackson were L.I.R.R. engineers in the late 19th and early

20th centuries. (Parmenus retired in 1927 I believe.)

I met Charlie in the early 1970s. He and his wife Lily lived in a

large, old house in Greenport that once belonged to his uncle. When I

knew him, he was suffering from the aftermath of a stroke, diabetes and

poorly healed (or performed) prostate surgery. He had a lot of trouble

speaking, but I was patient and learned lots of things from him. He and his

wife were very friendly to a young railfan, and I visited them many Sundays.

Charlie's claim to fame was being (unfortunately) the engineer of E51sa

camelback #2, the second locomotive of that infamous, eastbound

double-header that split a switch on Friday, August 13, 1926 (yes, Friday

the 13th for the superstitious) and plowed into Golden's Pickle Works,

located trackside in Calverton.

The engine crew of the lead locomotive, D16sb #214 died horribly as they

were pinned against the scalding hot firewall. Charlie and his fireman Bill

Squires were thrown clear, but injured. Charlie was flung from the cab

through the cab's skylight which, luckily, was open to get some air and

ventilation on that hot, humid, Long Island day in August.

Charlie said that instead of being taken to the hospital, he was brought,

with broken jaw, to the local police station and interrogated for hours.

Since he was the only surviving engineer, they attempted to blame him for

the disaster.

Bill Squires quit the railroad shortly thereafter, but Charlie stayed on

until retirement in the 1950s. As a result of the wreck, his mouth and jaw

were disfigured and his fellow workers nicknamed him "whalemouth." It

seems making fun of a man's disabilities was a blue-collar pastime even all

those years ago!

Charlie passed away in the late 1970s, and his wife Lily, who so diligently

took care of him throughout his illnesses, followed shortly after.

|

E51sa camelback #2, spun around

180 degrees and buried into Golden's Pickle Works - 8/14/26

C. T. Jackson Collection

Charlie as engineer at the throttle

of G5s #26 at Manorville, c. 1930

C. T. Jackson Collection

Charlie as a young fireman standing next to

H6sb #312 at Farmingdale in 1918.

C. T. Jackson Collection |

| The

Beginning of a Railfan

My father used to commute via the LIRR from Patchogue to his job as night

shift engineer at Piel Brothers brewery at 315 Liberty Ave. in the East New

York section of Brooklyn. He got to know most of the regular trainmen,

conductors and some engineers who had the various runs from that station.

My mother and I would, on occasion, meet my father at the station when my

mother had need of the car (back in those days, most everyone was a one-car

family).

One of those days was to be momentous for me...

I was about 5 years old and we were waiting on the platform in front of the

old, brick Patchogue station, watching for the eastbound train to arrive

with my father.

When the train arrived, he got off and so did Matty Roeblin, a trainman and

conductor on the LIRR. It was Matty's last day of service and his last

run. He had worked it as a trainman. He knew my father from

their friendly relationship developed over many years of commuting.

When Matty got off the train, he walked up to me alongside my father and

took off his blue serge trainman's cap with badge and his matching vest with

the brass "LI" buttons and handed them to me!

I was somewhat interested in trains around that time, and I guess my father

mentioned my interest in passing to him. When he gave me this

wonderful gift, I was hooked!

I wore them all the time. I even brought them to school in 1st grade,

and, with the assistance of a string of chairs, a paper hole punch and a

bunch of LIRR seat checks from another generous trainman-friend of my

father, the class would all sit in the chairs and I would hand out and punch

their "tickets" (seat checks), as we played train and I told everyone

to "change at Jamaica!"

My interest never waned, but got stronger as the years passed. This is

an example of what a generous deed and positive role model can do for a

child. I've loved the LIRR and everything about it ever since.

This photo is of LIRR Conductor Ed A. Martin and Trainman George Kennedy of

train #507 comparing their pocket watches in preparation of departing Oyster

Bay station in 1952. They are wearing the blue serge uniform with

brass buttons displaying the "LI" logo and their caps are displaying the

brass badges. It is this style cap and vest that I still have in my

collection and treasure the memories. (J. P. Sommer photo)

LIRR weekly commutation ticket used by my father from Patchogue to Flatbush

Ave., Bklyn., 1962. This ticket was purchased in Ronkonkoma, hence the

rubber stamp for "Patchogue". Had the ticket been issued at Patchogue, the

card stock would have been printed with "Patchogue" already on the ticket.

The ticket is pink. Pink designated tickets to Flatbush Ave., Bklyn.

Same commutation ticket, reverse side, showing the Ronkonkoma dater-die

indicating place of purchase of the ticket.

|

Railfan Dave Keller began his love for the LIRR at an early age. Here

we see Dave in 1952 at 8 or 9 months crawling as fast as he can behind the

old, brick Patchogue Depot to get his camera as a train is about to

arrive.

LIRR Conductor Ed A. Martin and

Trainman George Kennedy c1952

J. P. Sommer photo

Cap badge, lapel pins and

buttons from the 1950s

Dave Keller Collection

|

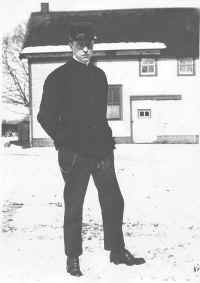

Railfanning

at "SG"

I first met George DePiazzy at a Boy Scouts of America function. I

was a young, volunteer Assistant Scoutmaster from Troop 80 in Holtsville, NY

and George was an Assistant Scoutmaster from a Bayport, NY Troop if I

remember correctly.

We got to talking and I discovered he was a block operator for the L.I.R.R.

and assigned to the 1st trick (shift) at "SG" cabin, which was located at

the time on the north side of the tracks and just west of 5th Avenue in

Brentwood. I also discovered that he was the father of two guys with whom I

had gone to high school.

I asked if I might visit him sometime while he was on duty and take some

photos. He said O.K. I visited "SG" cabin and George many times.

I photographed inside the cabin (it had a table block machine: no

Armstrong levers), and out, and took shots of trains getting orders, much as

I did at "PD".

Other railroaders nicknamed George "Dippy", not because he was stupid or

ditzy, but because of the way they would pronounce his last name: "Dippiazzy."

It eventually got shortened to "Dippy."

"SG" cabin was a tiny block office made of block and faced with brick,

replacing the old, wooden cabin south of the tracks and east of 5th Avenue.

George used to work that old cabin in it's last days, and described in

great detail how much "fun" it was having to use the old wooden outhouse, a

common site all over Long Island and the rest of the United States for that

matter.

George used to work "BK" block station at Stony Brook. Once, he was

sitting at the block operator's desk with his headphones on, talking to the

dispatcher during a thunderstorm. A lightning strike came through the

phone lines and went into his ears and blew him off the chair and across the

room, slamming him against the depot wall.

He had no recollection of this event, but was aware of it because he was

told what happened after he had regained consciousness. The story was

confirmed to me by witnesses.

George was an avid and experienced outdoorsman: hunter, boater, fisherman

and camper. He made a great Boy Scout leader. He and I attended

an adult training weekend together in 1972.

On Memorial Day, 1977 he was out fishing with a friend when he noticed a

small boat in trouble. It was stormy weather and the boat appeared to

be sinking. He and his friend put their boat in the water and went out

to assist the vessel.. The people in the boat were inexperienced, and

in attempting to save them, George and his friend banged their heads, lost

consciousness and drowned. He was 48 years old.

When the main line was electrified through to Ronkonkoma and double tracked

around 1987, "SG" cabin was no longer needed and was razed.

The first photo is of the old "SG" cabin c. 1925 looking west, photographed

by block operator James V. Osborne.

The second photo is of the "newer", relocated "SG" cabin looking west in

1969, prior to my having met George. The cabin was closed at the time

I photographed it (it was only open for 1 trick, Monday through Friday, I

believe) and the security shutters were closed. "SG" block signals are

visible in the distance.

The third photo is of operator George DePiazzy throwing the switch for the

long siding at "SG". I took this photo of George in 1972.

The fourth item is a memorial article from Newsday, dated 5/30/77 about the

men who died that day.

|

"SG" cabin c. 1925 looking west

J.V. Osborne Photo

Relocated "SG" cabin looking west in 1969

George DePiazzy throwing the switch for the

long siding at "SG"

Newsday Memorial Item 5/30/77 |

G.G. Ayling

and "CI"

In 1965 my mother bought me Ron Ziel's book Steel Rails to the Sunrise.

As a young railfan, I spent more time in that book than anywhere else.

Here were photos I had never even imagined existed.

I saw several of them were attributed to G. G. Ayling, the former agent at

Central Islip. Just out of curiosity, I looked in the phone book and

found him listed. I asked if I could visit with him and talk

railroading. He said yes, and that was the beginning of a very close

friendship that lasted until his death 8 years later.

George Graham Ayling was born in N. Y. City on 11/9/1888. His family

moved to Brentwood in May of 1893. As a young man he held various odd jobs

until unofficially starting on the railroad in September of 1909 at the

Brentwood Station. He lived where the present day Long Island

Expressway intersects with Brentwood Road. This was quite a hike on

his bicycle daily to go to work. He learned the freight and express

business along with telegraphy.

In June of 1910 he went to Quogue as a clerk under agent Ira Baker, who, in

later years, was the agent at Amagansett. George then worked a six-week

stint at Westhampton until he got furloughed.

He returned to the LIRR in April of 1911 and reported to work at Central

Islip as a clerk under agent Frank T. Kelly. Still living in Brentwood, he

would ride his bicycle to work and back daily, quite a distance, in all

kinds of weather. He would sneak it through the woods for access to

the Long Island Motor Parkway, to avoid paying tolls.

When Frank Kelly left the railroad, Vern L. Furman became agent, Henry

Nenstiehl became clerk and George became block operator. Back then, all

train movements were handled via telegraph and George became a very

proficient and fast telegraph operator. George was famous for his beautiful

penmanship and it showed, even when he copied a train order.

He must have figured he was here to stay, because he built his house a block

away from the depot in 1919 and lived there until he died.

George succeeded Furman as agent in May of 1923. He was to remain at

"CI" until his retirement on December 21, 1954.

He handled the regular commuter patronage and related baggage and express

duties, in addition to handling interline transactions whereby passengers

would be routed, by train, to just about anywhere in the country. In

addition to these duties, he had the added responsibility of handling the

Central Islip State Hospital with it's deliveries of freight, coal,

merchandise and passengers visiting via train and dead inmates leaving in

coffins. Work hours were from 6:00 am until work was completed,

usually around 7:00pm, 7 days a week.

When first employed, George earned $50.00 per month, with no overtime.

As operator he earned $87.50 per month, and as agent, about $100.00 per

month.

George loved photography and also photographed many scenes of the LIRR when

he was able so we had a common interest. I would visit him and his wife Emma

every Saturday. We would talk railroading, I would drive him and his

wife around, for it had been years since he had gotten out. He was very weak

and feeble of limb and had bad arthritis in his feet and hands. The

hands that wrote that beautiful penmanship were all gnarled and twisted, but

still he attempted to write beautifully.

George also attempted to teach me the American Morse code, the kind used in

railroad telegraphy. I never caught on very well. He would use a

regular telegraph key, and when he wanted to be very fast, a Vibroplex

mechanical key that he had purchased for his own use on the railroad. He

taught me fancy penmanship, told me all kinds of great stories about

railroad and non-railroad things on Long Island and overall we had a great

relationship. At one point, he suggested I call him "gramps" and he

became my adopted grandfather, having never known either of my own.

Then, Emma fell and broke her hip. Their kids hired a nurse to take

care of George. While Emma was in the hospital, George fell and

broke his hip. They were both in the same hospital at the same time,

on different floors. She came home, he didn't. He suffered

kidney failure and died on July 5, 1977, just shy of his 90th birthday.

His wife Emma died in February, 1983, also aged 89.

1. George G. Ayling reviewing express invoices - Brentwood - 1909

(G. G. Ayling collection)

2. Block Operator George G. Ayling in front of "CP" cabin - Central

Islip

1914. The cabin was never used, the railroad agreed to pay the

operator more per hour to handle ticket sales in addition to train

movements and moved him back into the depot. A bay window was

added to the depot for more office room. The cabin was loaded

onto a flatcar around 1916-17 and moved to Camp Upton where it

became "WC" cabin in use during W.W. I. (G. G. Ayling collection)

3. Assistant Station Agent George G. Ayling in uniform cap - Central

Islip

1918 (G. G. Ayling collection)

4. Central Islip station and block office - interior view -

December/1928.

(L. to R. Gene Costello, Clerk; Norman Mason, Block Operator;

George G. Ayling, Station Agent) (G. G. Ayling collection)

5. Central Islip station - looking west - December/1928 (same crew as

interior view)

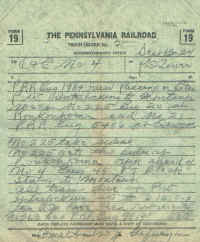

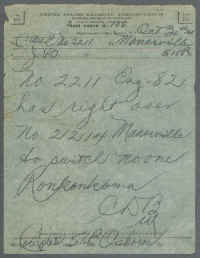

6. Form 19 train order issued at Central Islip - 7/26/41, in George

Ayling's

neat handwriting. The passenger extra mentioned running "PW" to

Montauk would be running from the end of double track at "PW"

cabin, west of Pinelawn on the Main Line to Montauk on the Montauk

Branch. This was accomplished via the Manorville Branch to

Eastport.

7. George G. Ayling in uniform cap with Vibroplex telegraphic key in

simulated block office created by Dave Keller - 6/71

(Dave Keller photo)

|

George G. Ayling reviewing express invoices

- Brentwood - 1909

G. G. Ayling collection

"CP" cabin - Central Islip 1914

Assistant Station Agent George G. Ayling in

uniform cap - Central Islip 1918

Central Islip station and block office -

interior view - December/1928

Central Islip station - looking west -

December/1928

Form 19 train order issued at

Central Islip - 7/26/41

George G. Ayling in uniform cap with

Vibroplex telegraphic key in

simulated block office created by Dave Keller - 6/71

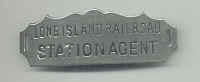

LIRR Station Agent badge - c. 1880s

(Worn by John Bonn, agent at Lindenhurst)

LIRR Station Agent badge - c. 1920s

(Worn by George G. Ayling, agent at Central Islip) |

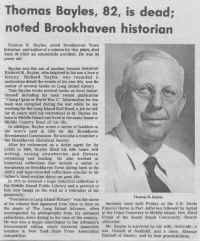

Tom Bayles

When I was about 15 years old, I was looking through the vertical files in

the reference section of the Patchogue Library and came upon a Brookhaven

Town historical pamphlet published by one Thomas R. Bayles of Middle Island,

N.Y. On the rear cover was a terrific shot of the Medford depot taken in

1940, prior to the grade elimination.

I mentioned the pamphlet and great photo to my father who said he knew Tom

Bayles, as he was the ticket clerk at Patchogue for years. He used to

give my father vegetables from his garden. (As mentioned in a previous

story, my father commuted on the L.I.R.R. from Patchogue beginning in the

late 1940s until his retirement in 1967.) Tom had since retired (1959)

after 45 years of service.

We looked him up in the phone book and he was still living in Middle Island.

My father renewed an old acquaintance and I created a new friendship with

both Tom and his wife Gertrude, which lasted for many years.

Thomas R. Bayles was born in Middle Island, N.Y. in 1895, the son of Richard

M. Bayles, a surveyor, realtor, notary public and, most importantly, Long

Island historian. Richard M. Bayles wrote and published the book

Sketches of Suffolk County in 1873 (I'm lucky to have a copy of this book, a

present from Tom.)

Tom followed in his father's footsteps in his love of Suffolk County history

and became the unofficial Brookhaven Town Historian, publishing loads of

pamphlets of Brookhaven Town history, most times at his own expense,

sometimes getting a bank or other business as a sponsor. Either way,

he would give these illustrated pamphlets away for free, in the hope of

creating interest in local history.

Tom Started as a ticket clerk on the L.I.R.R. in 1914. He would pedal

his bicycle daily from Middle Island to either the Miller's Place or

Shoreham stations, where he started out as a relief clerk during the summer

months. He would also deliver, by bicycle, Western Union telegrams

addressed to the townspeople of Shoreham, then pedal home again at the end

of a long day's work.

He was assigned to Westhampton in 1915 and had to get an automobile.

He left the L.I.R.R. for a several year stint on the New York, New Haven and

Hartford R.R. in Connecticut. He returned to the L.I.R.R. and worked

in the freight department at Camp Upton for 5 years starting in August,

1917. He was the last L.I.R.R. employee on duty when the freight

office closed on April 15, 1922. After WWI ended, he got permission

from the camp's commanding officer to take photographs. These are the

only known photos in existence today of the L.I.R.R.'s involvement at the

camp. His non-railroad shots of the camp are just as rare!

In later years he wound up at Patchogue, remaining there until his

retirement.

Tom often gave the impression of being a "country bumpkin", both in his

speech and mannerisms, but don't be fooled! He was a highly

intelligent and savvy man, especially when it came to business. He was

just quiet, liked to spend hours farming and went swimming frequently at

Cedar Beach in Rocky Point right up until his death. He and his wife

attended several churches every Sunday and they were both good people!

During the L.I.R.R. presidency of Thomas R. Goodfellow, retirees were given

"Lifetime" passes to ride the L.I.R.R. free of charge. Many times I

rode into Penn Station in Manhattan with Tom, on his pass, free of charge.

This courtesy was afforded us by fellow trainmen who knew him. He even took

me on a trip on the New Haven R.R. to Bridgeport, Connecticut and on the

Pennsy to Philadelphia, PA using this L.I.R.R. pass! Railroad men of

other roads used to afford this courtesy to each other, unofficially.

Tom's long and productive life came to an end on 6/29/77 when he was killed

in a automobile crash. His wife and their close friend were both

injured but not severely and survived.

1. 2nd depot building at Miller's Place - 1915 - photographed looking

east from the express platform by Tom Bayles as a young ticket clerk.

2. Shoreham station - 1912 - trackside view looking north. Tom

Bayles said this depot was very fancy, including wicker furniture in the

waiting room (T. R. Bayles collection, probably photographed by his brother

Albert Bayles, also a L.I.R.R. man and very good photographer. The

Medford shot that caught my attention was one if his!)

3. Shoreham depot plaza, showing, from L. to R.: freight house, North

Country Road grade crossing, depot and grounds and express house. Tom

Bayles climbed to the top of Nikola Tesla's abandoned experimental radio

tower in 1914 and shot this view looking north. He then went to the

other side of the tower and photographed the next shot.

4. Open touring car on unpaved Route 25A as viewed from Tesla's tower

- Shoreham, NY - 1914 (T. R. Bayles photo)

5. Tesla's tower and laboratory building as viewed from the Shoreham

station, looking south - 1914 (T. R. Bayles photo)

6. Westhampton station with returning Fourth of July crowd - 7/5/15.

View looking west from the express platform. Look at all those summer straw

hats! (T. R. Bayles photo)

7. Camp Upton station (tar-papered shack) - 1918 (T. R. Bayles photo)

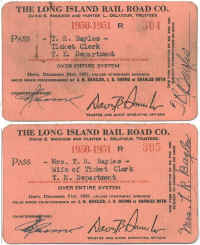

8. L.I.R.R. annual passes for Tom Bayles and his wife Gertrude for

1950-1951 (T. R. Bayles collection)

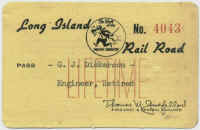

9. Example of a "Goodfellow"-era L.I.R.R."Lifetime" pass issued to

retired engineer George Dickerson - late 1950s (Jeff Skinner collection)

10. Thomas R. Bayles obituary from the Long Island Advance of 7/1/77

(The retirement date noted is incorrect. It should read 1959, not

1969)

|

2nd depot building at Miller's Place - 1915

Shoreham station - 1912

trackside view looking north

Shoreham depot plaza, showing, from L. to

R.: freight house, North Country Road grade crossing, depot and grounds and

express house

Open touring car on unpaved

Route 25A - 1914

Tesla's tower and laboratory building

L.I.R.R. annual passes for Tom Bayles and

his wife Gertrude

"Goodfellow"-era L.I.R.R."Lifetime"

Thomas R. Bayles obituary from the Long

Island Advance of 7/1/77

Westhampton station with returning

Fourth of July crowd - 7/5/15

Camp Upton station

(tar-papered shack) - 1918 |

The Pocket

Watch

Since railroading began, keeping to the timetable has always been a priority

for train and engine crews. Leaving a station late would make your

train late at your meet. The train waiting for you on the siding would

then be late as a result, and so on and so on. This could be

especially disastrous on a long distance run with many station stops and

meets. Engine crews would attempt to make up lost time by occasionally

exceeding the speed limit.

Time was a very important thing to railroad men and railroad men kept track

of this important commodity with a pocket watch; and not just any old pocket

watch, but a "railroad" pocket watch.

Old-time passenger train crews were required to wear a dress uniform of blue

serge wool in all weather, consisting of vest, jacket and cap, in addition

to a dress shirt and tie! Summer caps were issued that had a

ventilation mesh sewn around to allow some air to reach the head. That was

about the only concession to the summer allowed. (Even some engineers wore

neckties under their overalls!) Add to this constrictive clothing the

carrying of a heavy employee timetable, book of rules, fare tariff charts,

ticket stock, paper money and change, seat checks, ticket punch, ring of

coach and switch keys, and work must have been very uncomfortable especially

during a Long Island July and August!

In their vests the train crews wore their pocket watches. (Most men, prior

to the 1940s wore vests with their business suits as it was the style of the

times. Many wore pocket watches in those vests.)

The pocket watch was usually placed in one vest pocket and the watch chain

was looped through a buttonhole and set in the other pocket with some sort

of miscellaneous item on the end for weight, such as a small pen knife or a

special key or personal locket.

There was also another type of chain used which had a retaining bar at the

end. This bar would be slipped into one of the upper vest buttonholes

and the chain draped to one vest pocket where the watch resided.

Usually a decorative "fob" (ornamental piece of jewelry, etc. ) hung from

the upper portion of this style chain at the buttonhole level.. (I have a

fob from Jeff Skinner that was made by some skilled person who had cut the

LIRR keystone logo from two uniform jacket buttons of the 1940s and soldered

them together with a filler piece, attaching a ring at the top to allow the

fob be affixed onto the chain.)

Engine crews would wear their watches in the top pocket of their bib

overalls and attach the chain through a buttonhole sewn into the bib

specifically for that purpose. This provided an engineer quick and easy

access to his watch while seated at the throttle

Do you ever see the same style pocket watch for sale

on e-Bay but all the cases are different? Prior to about 1920,

watches were purchased separately from their cases. One would have a

certain amount of money to spend on a watch. Those for whom the

accuracy of the watch was tantamount, would purchase a certain costly

works from their local jeweler then choose a cheaper case from a catalogue

in the store. The jeweler would either have the case in stock or

would order the case whereupon he would then put the quality works inside

the case and you had your watch.

Others, to whom cosmetic appearance was more

important, chose an expensive case and, whatever money was left, purchased

a cheaper quality watch to have set in the case.

As the railroad pocket watch had to meet such strict

specifications, it was not a cheap item and needed to be placed in a

decent case due to the heavy use it would receive over the next 35+ years

of railroad use. Some cases were replaced as many as three times

over the lifetime of the railroad man’s career.

The railroad pocket watch was distinctly different from the ordinary pocket

watch in several ways:

First, it had a special 19, 21 or 23-jewel movement that was designed to

keep accurate time in 5 or 6 positions depending upon the model, as a

railroad man in train service (especially in freight service) could be

jostled and/or might be climbing, squatting, bending over, etc. while

performing his daily duties. A towerman would be throwing switch and

signal levers throughout his daily “trick.” A station agent or

ticket clerk would be lifting, loading and unloading baggage and express

items throughout their busy day.

Second, the front crystal (bezel) had to be removable, allowing access to

a small lever which, when pulled out, allowed one to set the hands of the

watch, the lever then being pushed back in and the crystal replaced.

This protected the hands from becoming "un-set" if bumped, etc.

while going through the gyrations mentioned above.

Third, the numbers on the face had to be large, bold, and easily readable

(no Roman numerals or tick-marks for the hours!)

There were many companies that manufactured

railroad-grade watches, such as

Elgin

and

Waltham

. One of the most popular and oldest ones was the Illinois Watch

Company. These watches featured the "Bunn Special," a

21-jewel movement designed for railroad use. Another of their models

featured a 60-hour movement! Arriving on the scene in 1893 was the

Hamilton Watch Company which produced their various railroad models i.e.

950, 992, 992B, et. al.

Hamilton

later bought out the Illinois Watch Company and continued to produce

high-quality railroad-grade pocket watches until their last run in 1969.

Railroad men had to submit their pocket watches every 6 months to a

railroad-approved jeweler who inspected, cleaned and set the watch according

to railroad standards. I guess all railroad men had to have an inspected

"back-up" timepiece during these inspections.

Crews would frequently set their watches by the "Regulator" depot clocks

hanging on the walls in every ticket office on the line. They would

also compare watches with each other to make sure they were all on the same

time. (Sort of like those old war movies where the soldiers would

"synchronize" their watches before going on a mission.) (See the photo

accompanying my earlier story "The Beginning of a Railfan" where we see

Conductor and Trainman comparing watches before leaving the station.)

As years passed, wrist watches took over as the timepiece of choice (and

convenience). Strict adherence to time became lax to such a point that

the radio would report daily on their morning traffic delays that the

railroad was running "on or close to schedule." A old, retired

engineer once told me that if he ever ran "close to schedule" he would have

gotten a reprimand and /or fine!

This is kind of ironic. A watchmaker recently told me that "railroad

approved" watches are no longer being newly manufactured because quartz

movements are so very accurate these days. We now have timepieces

accurate to the second and no longer require regular setting and adjusting

and "being on time" is no longer a number one priority to most people.

I guess the "old railroader" and the pocket watch are from a "time long ago

and a galaxy far, far away."

1. Illinois "Bunn Special" pocket watch manufactured in 1923 and given

to George G. Ayling by his wife Emma as a present upon his

promotion to Station Agent in 1923. George present this watch to

me in 1972 on my 20th birthday and I've treasured it ever since. I

still wear it in the watch pocket of my pants. (NO vests in Florida:

too hot!!!)

2. L.I.R.R. "Dashing Dan" leather watch fob used in lieu of a chain.

It

would hang out of your pocket for easy access, but it also allowed

one to lose their watch if they weren't careful. (Dave Keller

collection)

3. Engine crew of H10s #108 comparing watches at Holban Yard -

Hollis, NY - 11/26/54 (Edward Hermanns photo)

4. L.I.R.R. "Employees Certificate" indicating that the pocket watch

of

Trainman George Bookstaver had passed inspection.

(George Bookstaver collection)

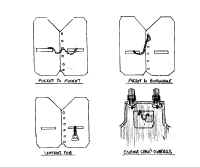

5. Positions in which the watch and chain or fob could be worn in

vests

and overalls. (Sketch by Dave Keller)

6. My Seiko quartz "Railroad Approved" wrist watch of the 1990s which

I

still wear daily. (The most accurate timepiece I've ever owned!)

|

Illinois

“Bunn Special pocket watch manufactured in 1923. (A railroad watch

had to be accurate to within 30 seconds a

week.)

Illinois

was bought out by

Hamilton

in 1927.

Another fine pocket watch that was carried

by railroad men was the

Hamilton

Railway Special.

Several models were available and one of the most popular was the 992,

followed some years later by the 992B.

The above watch is a model 992, with a serial number that dates its

manufacture to 1915. It has 21 jewels and is adjustable to temperature

and 5 positions. (The later, 992B was adjustable to 6 positions.)

It hosts a

Montgomery

dial, where all the minutes are indicated as numbers in lieu of “tick”

marks as well as a bar-over-crown case. (The second-hand in this scan

appears to be broken, but it was actually moving when the scan was made and

the scanner does not stop action.)

Close-up of a later, similar case depicting

the bar-over-crown style.

L.I.R.R. "Dashing Dan" leather watch fob

Engine crew of H10s #108 comparing watches

at Holban Yard - Hollis, NY 11/26/54 (Edward Hermanns photo)

L.I.R.R. "Employees Certificate" indicating

that the pocket watch of Trainman George Bookstaver had passed inspection.

(George Bookstaver collection)

Positions in which the watch and chain or

fob could be worn in vests and overalls. (Sketch by Dave Keller)

Seiko quartz "Railroad Approved" wrist watch

of the 1990s |

Railroad

Telegraphy

Before the days of telephone, radios, cell phones and Nextel-type

radio/phones, there was Morse code. This was named, of course, after

it's inventor, Samuel F. B. Morse (who sent the very first telegraphic

message in 1844 to wit: "What hath God wrought?")

Messages had to be sent both quickly and accurately and the only thing that

came to mind at first was a series of horse riders running messages in

relays from one station to another outwitting bandits and Native Americans

along their routes. We know this as the Pony Express. It

received much glamour in the movies and stories, however, the Pony Express

lasted only one short year. It was put out of business by Mr. Samuel

F. B. Morse's invention.

The Morse code sent messages electrically (via wet-cell battery) through a

wire using a series of dots and dashes which represented letters and

punctuation. The telegraph operators had to learn this new "language"

and interpret it.

Retired LIRR station agent George G. Ayling told me that a telegrapher

didn't listen to individual letters, but, rather, listened to and

anticipated entire words. (Sort of how we hear conversations. We don't

hear letters at a time, but entire words. And if you've never had your words

anticipated, just try talking with your wife!)

Cutting through the general history lesson, and to make what could be a very

long story short, telegraphy became the main means of communication on the

railroad, as well as throughout the United States and the world and was used

on American railroads well into the 20th century, long after telephones were

in common use! Kind of tells you of it's reliability and the

confidence that people had in the system.

The LIRR was no exception. Not only were Western Union telegrams

received and sent at the local ticket offices, as a service to the

community, but the system of dispatching trains via train orders (both Form

19s and Form 31s) was done via the telegraph. (Note: a Form 31, for you

youngsters, was a train order which the train crew did not catch on the fly

from a "Y" shaped stick, or hoop, but had to stop and sign for it! For

obvious reasons, they were not around for long)

The Dispatcher's office (at first in L. I. City, and after 1913, in Jamaica

when the railroad's general offices were moved) would send out a train order

to an individual station.

The telegraph system was like one big party line (again for the youngsters:

a party line was the old rural telephone service whereby you picked up your

phone and could hear other people on the same line talking. You had to

cut in to make your call: "Edna, please get off the phone! I

have to call Dr. Johnson!" or: "Ruthie! Did ya hear? Molly

Stevens is having an affair with the ice man!" ). Every station along

the line would hear the tap-tapping all day long of messages

going to various block offices. The operators learned to block out all

the messages that weren't for them. They would perk up once their

Telegraphic Call Letters were sent over the wire. They would then get

on the wire and respond by repeating their call letter to acknowledge that

they were present and ready to copy a train order or take a telegram.

Every station and block office had it's own distinctive call letters. Some

had separate letters for the telegraph and block offices, such as Patchogue.

Originally "P", it became "PG". When "PD"

tower was opened and the block office moved from the depot building, the station

retained "PG" for telegrams and the block office used "PD" for train orders.

As if listening to all that tapping all day long wasn't bad enough, the

operators would put their sounder, that part of the telegraphic equipment

that received and "sounded out" the message, into a wooden contraption

called a resonator. This would capture the sounds and focus them

towards the ear of the operator sitting at his desk. To increase that

sound even further, the operator would sometimes flatten out a metal tobacco

tin, and jam it behind the sounder in the resonator!

The telegraph key was firmly screwed to the desk top and, contrary to

popular belief and as portrayed in movies, was not tapped with one or two

fingers, but grasped firmly with at least 2 fingers and thumb, and held

firmly while sending the message.

Telegraphers who wanted to be "speed demons" could purchase, at their own

expense, a "bug." This was the nickname given to the Vibroplex

"Lightning Bug" model of mechanical telegraphic key. Instead of the

conventional and wrist-straining up and down movement, this key went side to

side. If the operator wanted dashes he held the key to one side. If he

wanted dots, he held it to the other side, and to speed up the process, if

he held the key to the dot side, he would get a steady stream of dots, sort

of like holding down a key on an electric typewriter or computer keyboard

and the key repeats itself until you let go.

Operators got to know other operators' style of sending, which they referred

to as their "fist." They would hear someone's "fist" and know immediately

who the person was before they even identified themself.

The operators also had to take a test every so often to make sure they were

up to snuff in sending and receiving accurately. They also had their own

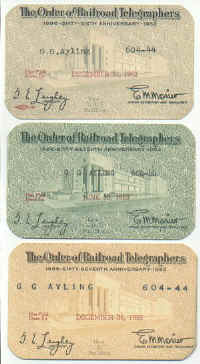

union. The O.R.T. or Order of Railroad Telegraphers represented block

operators on the L.I.R.R.

(All illustrations are from G. M. Dodge's 1911 handbook

The Telegraph Instructor unless otherwise noted)

1. The Morse Code used on the railroads and in Western Union offices

was the American Morse Code. This code differed from the International

Morse Code, in that the American code inserted spaces between dots in some

letters and numbers and punctuation were different. I believe the two

codes were designed purposely to be different so there could be no

confusion. These pages show the differences between the two alphabets

and numbering and punctuation systems.

2. Title page to G. M. Dodge's 1911 handbook The Telegraph

Instructor.

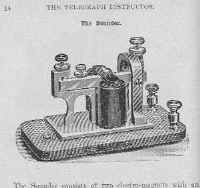

3. Engraving of a typical telegraph key

4. Engraving of a typical telegraph sounder

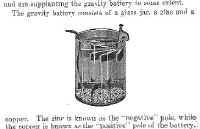

5. Engraving of a typical telegraph wet-cell battery, usually kept

under the operator's desk. Lots of liquid battery acid there!

6. Drawing of a main line telegraph circuit

7. Order of Railroad Telegraphers membership cards - 1952-53

for George G. Ayling, L.I.R.R. station agent at Central Islip

(G. G. Ayling collection)

8. LIRR Union pins. Order of Railroad Telegraphers is in the

center of the display (the sounder within the wreath)

(J. Skinner and G. G. Ayling collections)

|

American Morse Code used by

railroads and telegraph offices

International Morse Code

Title page to G. M. Dodge's

1911 handbook

The Telegraph Instructor

Typical telegraph sounder

Typical telegraph keys

Typical telegraph wet-cell battery

Main line telegraph circuit

Order of Railroad Telegraphers membership

cards - 1952-53

George G. Ayling

LIRR Union pins |

| The

Manorville Branch

This line was originally the

Long Island Rail Road ’s Sag Harbor

Branch until the South Side Rail Road was merged into the L.I.R.R. and its

South Side Division which had been extended from Patchogue eastward was

connected with the L.I.R.R. west of Eastport. The L.I.R.R. depot at

Moriches, now located along what was to become the Manorville Branch, just

south of South Country Road crossing was moved further east and became the

new Eastport station.

When the L.I.R.R. was extended from

Bridgehampton eastward to Montauk in 1895, the Sag Harbor Branch became only

that spur from Bridgehampton to

Sag Harbor. What had been

the original Sag Harbor Branch was now called the Manorville Branch,

connecting Manorville (previously Manor) on the

Main Line with Eastport on what would now be called

the Montauk Branch.

Manor, originally called Punk’s Hole and

later, Manorville, was a very important junction.

There was a depot building containing the block office whose

telegraphic call letters were designated “MA”, a water tower, and the

longest passing siding on the entire railroad system. On

8/5/16 “MR” cabin was

opened just west of the depot at the switch to the junction and the block

operator was moved from the depot to the cabin.

That same year a similar block

cabin was installed at Eastport Junction and designated with the telegraphic

call letters “PT”.

Originally, trains bound for

Montauk would, on occasion, be routed through the

Main Line , and then cut across to the

South

Shore

via this branch. Other trains, such as the “Scoot” would run from Greenport

west to Manorville, make a reverse move at the junction and head back east

again over the Manorville Branch to Bridgehampton and Sag Harbor and return.

These reverse moves at

Manorville ended when the wye was installed there in 1887. There was also a

wye installed at the connection to the Montauk branch at Eastport but not

until 1917.

The Eastport wye wasn't actually

a wye in the true sense of the word, in that the Manorville branch was

pretty much a straight run to Eastport and the Montauk branch made a

sweeping curve west of the junction at Eastport. The west leg of the "wye"

at Eastport connected further west of the junction. It was more of a spur

off the Manorville branch.

These wyes allowed ease of

movement in all directions, such as coming from Greenport and "rounding the

horn" to head to Sag Harbor and vice versa, or routing trains from Camp

Upton east to Manorville, then west on the Montauk branch.

I was told by a WWI-era block

operator that troop trains were sent eastward over the Main line to Camp

Upton and the empties sent further east to Manorville, then via that branch

to Eastport and then back west.

This way there could be a

constant flow of eastbound troop trains to the camp and a solid flow of

westbound empties, or troop trains filled with newly-trained soldiers

("doughboys") headed westbound without any right of way issues, and any time

wasted "going in the hole" for anyone else!

One big circuitous route!

Also, the wyes were curved

broadly enough to allow this to be done at a fairly good speed.

In the early days, the

"Cannonball" consisted of a two-part train (double consist of cars). It was

pulled eastbound towards Greenport along the

Main Line .

At Manorville, the train was cut

in two. The first half continued on to Greenport. The second half coasted

onto the Manorville branch and coupled with a waiting locomotive(s) for

continuation on to Montauk! This (OSHA look the other way) was done without

stopping and passengers on board!

It was explained to me by an old

railroader many years ago that the engine(s) waiting on the Manorville

branch were idling, ready and waiting. As the first half of the train

approached the junction, the 2nd half of the cars were cut loose. The

engineer was given a signal and he accelerated out of the way.

As he cleared the switch to the

junction, the operator would throw the switch and the coasting cars, most

probably being manually braked by the brakeman would enter the Manorville

branch.

The locomotive(s) waiting for

these cars would then begin to move eastward along the branch, just fast

enough to stay ahead of the coasting cars. The cars would then gently couple

into the rear of the locomotive(s) tender(s).

No thumping, no banging, no

whiplash-producing moves. Just a clean flow.

As I said: railroading skill at

it's finest!

I wish I was there to see it. (I really wish I was there to photograph

it!!!!)

The L.I.R.R. shut down the

Manorville Branch in 1949 and was quick to tear up the tracks!

A railroader around at the time this was done told me that it was the

L.I.R.R.’s position that they were saving lots of money in salvaging the old

rail for use elsewhere. (Where???)

The depot building at Manorville

along with “MR” cabin and the junction connection were removed that same

year and a concrete shelter-shed erected for passengers. The west leg of the

wye at Eastport was taken out of service much earlier, on 2/19/31. “PT”

cabin at Eastport was closed in September of 1938 and the block signals

removed.

The LIRR made a major mistake

shutting the Manorville branch down in 1949. No one seemed to plan on future

growth and needs! Also, no one seemed to realize or to think it was

important that there was no way to get from the

Main Line to the

South

Shore unless one traveled all the way back

into Nassau County, going miles out of the way.

Explanation of illustrations:

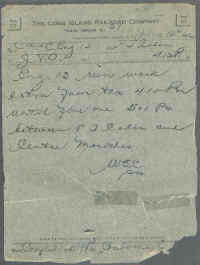

1. Form 19 train order issued at

“PD” tower, Patchogue in 1934 showing a Montauk bound train running extra,

being routed via the Main Line from “PW” cabin west of Pinelawn eastbound

via the Manorville Branch to “MY” (Montauk’s call letters)

(Dave Keller collection)

2. Block

Operator James V. Osborne standing outside “MR” cabin – Manorville - 1921.

(view looking east towards the junction and depot)

(Copy from a photo given to me personally by Jim

Osborne. Original negative in

the collection of Ron Ziel)

3. Form 19

train order issued by operator James V. Osborne at “MR” cabin – Manorville

–1921 (J. V. Osborne collection)

4. Form 19

train order issued by operator James V. Osborne at “PT” cabin – Eastport –

1922 (J. V. Osborne collection)

5. Close-up scan of

“PT” cabin viewed from signal mast looking west up the Manorville

Branch (straight ahead) with Montauk Branch curving off to the left – 1923

(J. V. Osborne photo)

6. View of

the signals at Eastport Junction looking east from the Montauk Branch

towards “PT” cabin. The

Manorville Branch is coming in on the left – 1923 (notice which branch had

the right of way!)

(J. V. Osborne photo)

7. Similar

view only looking east from between the Manorville and Montauk Branches –

1923 (J. V. Osborne photo)

8. E51sa

camelback #4 pulling the “Cannonball” eastbound on the Manorville Branch

approaching Eastport Junction – 1923 (view looking west from signal mast.

Montauk Branch curving off to left)

(J. V. Osborne photo)

9. E51sa camelback #?

pulling eastbound train off the Manorville Branch at “PT” cabin – Eastport –

1923 (view looking west)

(J. V. Osborne photo)

|

Form 19 train order issued at “PD” tower,

Patchogue in 1934

“MR” cabin – Manorville - 1921

Form 19 issued at “PT” cabin Eastport 1922

Form 19 issued at “MR” cabin

Manorville 1921

“PT” cabin viewed from signal mast looking

west up the Manorville Branch (straight ahead) with Montauk Branch curving

off to the left – 1923

Eastport Junction looking east from the

Montauk Branch towards “PT” cabin.

The Manorville Branch is coming in on the left – 1923

Looking east from between the Manorville and

Montauk Branches – 1923

E51sa camelback #4 “Cannonball”

eastbound on the Manorville Branch approaching Eastport Junction – 1923

E51sa camelback #? eastbound train

off Manorville Branch at “PT” cabin

Eastport – 1923 |